Attitudes Towards Deafness: American Sign Language v. Oral School

Melanie Grasso reinforces the importance of acknowledging Deafness as its own culture, utilizing sign language to create community especially for young learners.

Introduction:

More than ninety percent of Deaf children are born into hearing families. After receiving their child’s diagnosis, parents are tasked with the decision of selecting an educational path: American Sign Language (ASL) centered programs or oral schools, which focus on mainstreaming students and eschew ASL education. The language used to describe the Deaf community in both schools accentuates a contrast in ideologies; while signing schools view Deafness as a “difference,” oral schools interpret it as a “disorder.”

To many parents unfamiliar with sign language and the deaf community, a Deaf diagnosis is frightening. Parents worry their children are bound to an isolated trajectory with doomed outcomes. While studies show that Deaf parents expose their children to conventional sign language early in life, hearing parents often hesitate to welcome a new culture into their households, fearing that they will be unable to share their own language and culture (Marshark, 2007). Marc Marshark, director of the Center for Research, Teaching, and Learning at the Institute for the Deaf at Rochester Institute of Technology, presents testimony depicting the commonality of this hearing parent-Deaf child disconnect. As Marshark explains, “parents unfamiliar with Deafness will have particular challenges in raising their Deaf children... such parents typically will not take the time to learn and consistently use alternative methods of communication, even when they are clearly needed” (Marshark, 2007). Language is a joint experience amongst speakers, facilitating connection. Families pride themselves on passing down their culture from one generation to the next. Breaking a generational pattern can appear overly daunting, potentially leading to decisions neglecting the child’s best communicative interests.

Individuals such as Meredith Sugar, the former President of the Alexander Graham Bell Association for Deaf and Hard of Hearing, prey on hearing parents’ fears by promising an oral education approach will return their child to “normal.” In “Ethics rounds needs to consider evidence for listening and spoken language for Deaf children” (2015), Sugar presents potential evidence to support the use of listening and spoken language (LSL) for Deaf children and encourages abandonment of ASL. Sugar references studies stating that “children who follow an auditory-verbal (A-V) communication approach (solely by using LSL, and not ASL), demonstrate better LSL skills than do children who follow a total communication approach using both LSL and ASL” (2015). Sugar’s argument focuses on mainstreaming deaf children and encourages the use of oral methods to avoid the challenges of learning another language. While focusing on the improvement of LSL skills, she fails to compare the successfulness of ASL approaches in assimilating students into Deaf culture. Sugar neglects to mention the isolation that Deaf children educated by oral approaches often experience compared to the community they find within Deafness (Ladd, 2013). Additionally, studies demonstrate that ASL approaches provide a more effective overall education for deaf students (Hall, 2017).

Sugar’s terminology regarding the Deaf community is widely considered controversial, which prompted her removal from the Alexander Graham Bell Association. Joshua Marsh, a Deaf individual, posted a successful petition to Change.org in protest of Meredith Sugar’s position as President of the Alexander Graham Bell Association for Deaf and Hard of Hearing. This petition called for accountability regarding her “audist” attacks against the Deaf community, referencing statements such as “Deaf children are actually a part of hearing culture,” and “ASL is merely an option for deaf children.” The petition gathered over 1,500 signatures, resulting in Sugar’s termination. Sugar’s anti-ASL approach is connected to an audist mindset that views Deafness as an unfavorable disability that can be corrected, encouraging the view that people who are Deaf are disordered.

Wyatte Hall, a research assistant Professor at the University of Rochester Medical Center School of Medicine, has challenged this thinking. Hall discusses language deprivation within Deaf children who are not taught ASL:

“A long-standing belief is that sign language interferes with spoken language development in deaf, children, despite a chronic lack of evidence supporting this belief. This deserves discussion as poor life outcomes continue to be seen in the deaf population... Brain changes associated with language deprivation may be misrepresented as sign language interfering with spoken language outcomes” (2017).

There is no empirical evidence supporting the harm of sign language exposure. Instead, there is growing proof that lack of sign language access has negative implications (Hall, 2017). These negative implications include “cognitive delays, mental health difficulties, lower quality of life, higher trauma, and limited health literacy” (Hall, 2017). Oral schools dismiss this research, promoting fear of deafness and providing merit to the idea of cultural assimilation.

In addition to disregarding the educational benefits of sign language, Sugar and other anti-ASL protesters fail to recognize that signing serves as a bridge to the vibrant, powerful Deaf community. Through ASL, deaf students discover their identity and connect to a shared culture. The term “Deaf identity” implies that Deafness is its own culture, utilizing sign language despite outcry from the wider “hearing world,” which views it differently than those inside it do. While spoken languages create community among those who speak them, ASL creates both a community within and a bridge to the hearing world. As encapsulated by Jemina Napier, Professor of Intercultural Communication at Heriot-Watt University, “the recognition of the full linguistic status of sign languages was transformative in enabling researchers to shift perceptions of deaf people as outsiders in a hearing world to people with a sense of belonging, who identify with one another based on shared experience and the use of a sign language.” (Napier & Leeson, 2016). The recognition of American Sign Language as an established language was a critical step towards the hearing world’s embracement of Deaf people as a community rather than disabled.

Field Research:

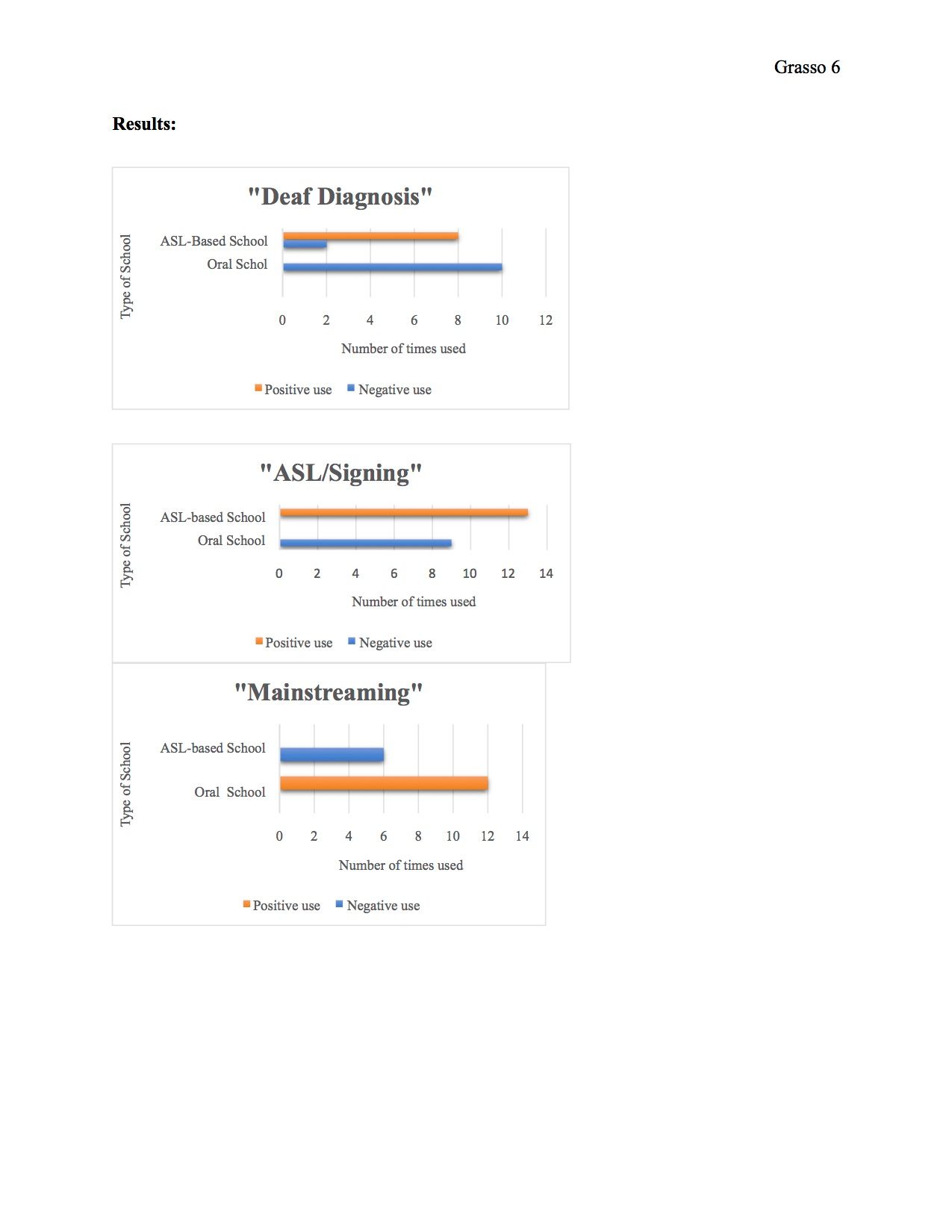

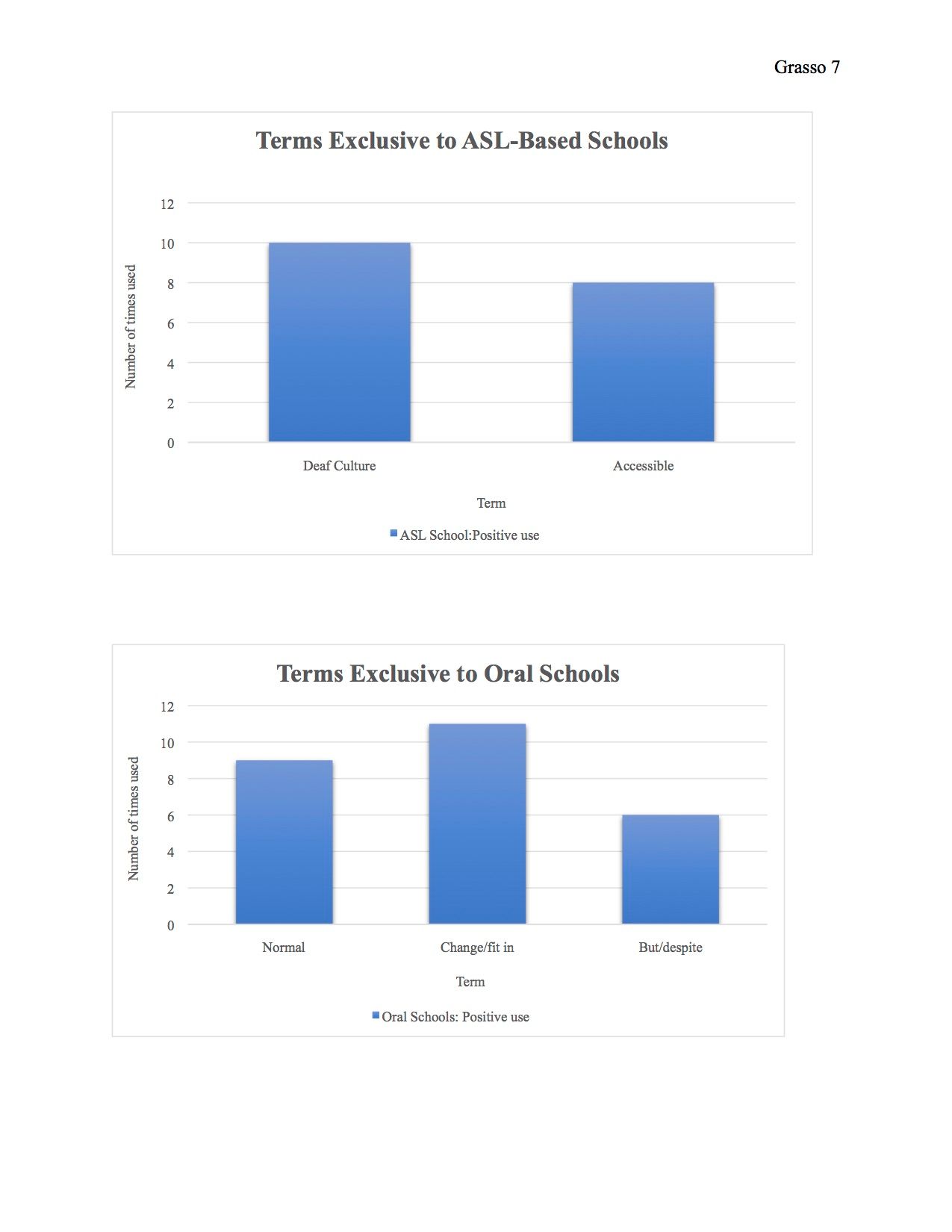

Testimony from oral-centered schools and ASL-centered schools was gathered from videos and mission statements on their official websites. Data was collected from ten individuals representing each school: 10 oral school testimonies, and 10 ASL school testimonies (derived from teachers, alumni, students, and parents). Each person’s word selection was analyzed along with the word’s intent, noting commonalities and differences between the two schools. Tallies for each target word/phrase spoken are displayed below. Each phrase is divided by positive verses negative usage.

In oral schools, ASL carries a negative connotation. A deaf diagnosis is described as something to be feared, and mainstreaming children at whatever cost to fit society’s standards of normalcy is emphasized. One mother states that her Deaf child, through the oral school, has the chance to be “like the normal kids” (MOSD, 2017). “A bright future” is discussed by parents praying that their child will eventually assimilate and be like their hearing peers. In ASL schools, however, the “bright future” emphasized by faculty is the idea of students becoming educated, compassionate citizens that also speak ASL. A Deaf diagnosis is filled with, in some cases initial shock, but ultimately, hope. Free ASL classes are offered to family and friends who wish to learn the language. In ASL schools, an emphasis is put on embracing Deaf culture and celebrating the community sign language brings. The terms “accessibility” and “Deaf culture” are repeated throughout their remarks. Comparatively, Oral schools do not mention Deaf culture or the Deaf community, instead pushing forth the narrative that sign language acquisition will isolate children. The use of “but” and “despite” as employed by the Memphis Oral School for the Deaf in contexts such as “I adopted my son from China despite his Deafness” and “my daughter is Deaf, but she loves to play with her friends” (MOSD, 2017), display Deafness as an unfavorable handicap. Audist language pushing for “change” underlines all oral commentary. Anti-Deaf language was not used in ASL-based testimonies.

Discussion of Findings:

By comparing the language used by individuals supporting oral schools to that used by ASL schools, the different perceptions about Deafness become evident. ASL-centered schools praise the Deaf community and encourage students to embrace its culture whereas oral schools describe Deafness as a separate entity from the person themself, an entity that needs to be fixed in order for the person to live a successful life. Oral schools see deafness as an obstacle to overcome, one that will cause a child to lead a burdensome life if untreated. ASL-teaching schools, alternatively, view deafness as a proud part of one’s culture and character. Sign Language supporters consider Deaf individuals from a cultural and linguistic perspective rather than a disability perspective. The two different thoughts produce students that either hide or embrace their Deafness.

Conclusion

While a child’s diagnosis of deafness is alarming for hearing parents lacking prior knowledge of Deaf identity, it is crucial for parents to look beyond bias in order to set their child up for success. Oral Schools for the Deaf and the ASL schools represent opposite attitudes regarding what success looks like. Oral schools support a “disorder” thesis of fixing the “problem” of Deafness whereby ASL schools implore Deaf individuals to welcome their community by learning sign language, learning about Deaf history, and celebrating their culture.

As Richard Meier states in “Sign Language Acquisition,” “the child’s parents may have no knowledge of a signed language and, in some cases, have been actively discouraged their child from learning one. These Deaf children of hearing parents thus confront a serious interruption in the generation-to-generation transmission of language” (Meier, 2016). Parents conditioned into viewing Deafness as a disorder are at risk of subjecting their children to language deprivation. Sign-language based education provides both connectedness to the Deaf community and an improved sense of self. Nikolaraizi’s study analyzes the educational experiences of 25 Deaf adults in relation to their identity. The qualitative analysis indicated that the most critical educational experiences for the participants' identity concerned their interactions with hearing or Deaf peers and their language of communication with their peers at school. When parents select an oral school approach, they prevent their child from entering a more educationally efficacious and culturally rich environment. As proven in Nikolaraizi’s study and Meier’s literature review, Deaf children receive neither an educational advantage nor a cultural benefit from being forced into spoken language.

The testimony discovered throughout the research and studies of others proves that the reasoning for oral approaches is rooted in a desire to assimilate children to fit society’s standard of success. In actuality, success takes different forms. Forcing all individuals into one rigid scale detailing the “proper way of life” is damaging to people with varying abilities. As explained in “Sign Language Studies,” the Deaf community has felt the need to escape the “reductionist lens of definitions created by oppressors” (Ladd & Lane, 2013) much in the same way other minority communities such as women, LGBTQ+, and people of color have. Communication is broad, and self-expression should be encouraged rather than used to assert a standard that mocks outsiders. Contrary to messages promulgated in oral schools, community and connection are not exclusive to spoken language. American Sign Language provides children with a rich and colorful language, connection to the Deaf community, and a bridge uniting the hearing world and Deaf world.

References:

Hall, W. C. (2017). What you don’t know can hurt you: the risk of language deprivation by impairing sign language development in Deaf children. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21, 961–965.

Ladd, P., & Lane, H. (2013). Deaf ethnicity, Deafhood, and their relationship. Sign Language Studies, 13(4). 565-579. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26191740

Marschark, Marc. (2018). Raising and educating a Deaf child: a comprehensive guide to the choices, controversies, and decisions faced by parents and educators. Oxford University Press.

Marsh, J. (2015, September 23). Petition for the resignation of Meredith Sugar, President of AGBA. Change.org. https://www.change.org/p/meredith-sugar-petition-for-the- resignation-of- meredith-sugar-president-agba.

Meier, R. P. (2016). Sign Language acquisition. Oxford Handbooks Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935345.013.19

Memphis Oral School for the Deaf. (2017, September 23). https://mosdkids.org/.

Napier, J., & Leeson, L. (2016). Sign Language in action. Sign Language in Action, 50–84. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137309778_3

New York School for the Deaf. (2021, March 14). https://www.nysd.net/about.html

Nikolaraizi, M. (2006). The role of educational experiences in the development of Deaf identity. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 11(4), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enl003

Smith, J., & Wolfe, J. (2016). Should all deaf children learn sign language? The Hearing Journal, 69(2), 18. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.hj.0000480888.40462.9b

Sugar, M. K., & Goldberg, D. M. (2015). Ethics rounds needs to consider evidence for listening and spoken language for deaf children. Pediatrics, 136(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3106a

Sutton-Spence, R. (2010). The role of sign language narratives in developing identity for Deaf children. Journal of Folklore Research, 47(3), 265. https://doi.org/10.2979/jfolkrese.2010.47.3.265

Mel Grasso is a junior Speech-Language Pathology major and Language Sciences minor at Marymount. She is passionate about communication, language accessibility, and her dog, Mai.